Coastal Voices: 2020-Present

Please read about our work in our various communications including; story books, research updates, reports, scientific articles, podcasts and more! You can also read about Coastal Voices’ work in the news.

Latest Events and Activities - Sept 2025.

Native Alaskan carved sea otter (1885). Image courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

Book Chapter: A catastrophic and unintended experiment: Revising our understanding of sea otters and their social and ecological importance based on a system in transition

Tim Tinker et al. 2025; This book chapter describes the history of sea otter removal during the industrial fur trade, their subsequent reintroduction to coastal habitats, and how these two disruptions were unintended ‘experiments’ that have revealed important insights into the role of sea otters and people in coastal ecosystems. This chapter pulls together archaeology, community ecology, population biology, genetics and social-ecological systems to describe what we have learned, and what relationships have yet to be restored. Members of our Coastal Voices research team are authors. Read the paper.

Arianne Augustine (2024).

Scientific Article: Insights gained from including people in our models of nature and modes of science.

Anne Salomon & Iain McKechnie, 2025; This paper challenges the idea that humans are separate from marine ecosystems rather than part of them. We detail the many ecological functions and reciprocal relationships that exist between people and marine ecosystems, and have been practiced for millennia. The authors, Anne & Iain, are part of our Coastal Voices research team. Read the paper.

Story Book of Coastal Voices Gathering Hosted by Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k:tles7et'h' Nations - July 2024.

Timeline of Recent Activities and Updates - May 2024.

nicole marie burton (2024).

Scientific Article: Relational place-based solutions for environmental policy misalignments.

Hannah Kobluk et al. 2024; This paper describes how our dominant structures and processes for resource management do not match the ecosystems they are intended to manage. Instead place-based Indigenous-led examples of caring for relationships offer us a hopeful pathway of how to manage for resilient relationships into the future. Members of our Steering Committee and research team are authors on this piece! (Read the paper)

Morgan Holder (2024).

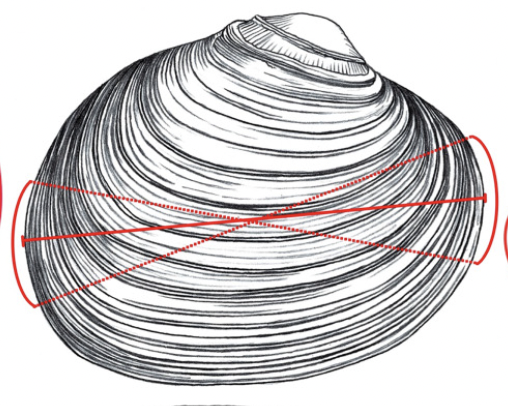

Scientific Article: Estimating size-at-harvest from Indigenous archaeological clamshell assemblages in Coastal British Columbia

Dylan Hillis et al. 2024; This paper develops a method for calculating full clam shell size from shell fragments. This method can be used on archaeological shell fragments found in ancient middens to determine what size of clams First Nations were harvesting in deep time. We test the method on ancient clams from Tseshaht territory and find that clams harvested 3000 years ago were similar in size to modern day size limits, suggesting people have been sustainably harvesting shellfish for millennia. The authors include members of our research team! Read the paper.

Arianna Augustine (2023).

Scientific Article: Disrupting and diversifying the values, voices and governance principles that shape biodiversity science and management

Anne Salomon et al. 2023; This paper describes governance principles of 17 Indigenous Nations from British Columbia and how they can be mobilized to monitor and manage biodiversity in more inclusive ways, using the recovery of sea otters as an example. This authorship team includes the Steering Committee and research team of Coastal Voices (Read the paper; Read the press release)

Scientific Article: Ancient evidence of low sea otter prevalence on the Pacific Northwest coast

Erin Slade et al. 2021; This paper affirms Indigenous knowledge that, for millennia, people managed their relationship with sea otters and shellfish to maintain access to food. Using archaeological data and modern ecological data in places with and without otters, this paper compares California mussel sizes across time. There was a much broader size range of mussels in archaeological sites than in areas with otters today, which indicates that Indigenous communities maintained access to large mussels for 1000s of years (effectively excluding otters which would otherwise eat these large mussels). (Read the paper)

Coastal Voices Phase 1: 2014-2020

Final Report: Lessons Learned and Recommendations on Revitalizing our Relationship with Sea Otters, Kelp Forests and Coastal Fisheries

After working together since 2014, this report sums up all of the work from our research collaboration to inform how coastal communities can protect their seafood and support thriving coastal ecosystems with the recovery of sea otters. It touches on the challenges and opportunities associated with sea otters, and highlights the key findings from ancestral knowledge, interviews, and field studies. It also provides policy recommendations and next steps for research collaboration, which now form the basis of the next phase of Coastal Voices. (Read the report here)

BOOK CHAPTER

First Nations Perspectives on Sea Otter Conservation in British Columbia and Alaska: Insights into Coupled Human Ocean Systems

Highly valued, hunted, controlled and traded by indigenous people for at least 12,000 years, sea otters and humans along North America's northwest coast share a deep history. This book chapter synthesizes archaeological evidence, historical records, traditional knowledge and contemporary ecological data to illuminate how coastal First Nations used, managed and conserved sea otters and our shared ocean home. (Read the book chapter here)

Through the lens of Western science and traditional Native knowledge, art and photography the authors uncover the ecological, social and economic causes of coastal ecosystem change on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula. The reader is offered a rare opportunity to share experiences, perspectives and knowledge of Sugpiaq Elders and village residents whose lives and intuitions are shaped by the rhythms of the sea. This collaboration illuminates the resilience and limits of marine ecosystems and the vast archive of knowledge and expertise held by different cultures. (Read the book here)

In 2014, the Coastal Voices team hosted a workshop 4-day workshop attended by Indigenous Chiefs, community leaders, and knowledge holders representing 19 Indigenous Nations and Tribes across B.C. and Alaska. The overarching goal of this workshop was to examine the ecological, socio‐economic and cultural trade‐offs triggered by the recovery of sea otters through the lens of traditional knowledge and western science to better equip coastal communities with shared knowledge and ecosystem‐based strategies to navigate the profound transformations that occur with the recovery of this predator. (Read the report here)

PODCAST

Kelp Worlds: Ocean People

This podcast by Future Ecologies features Dr. Anne Salomon, K_ii’iljuus Barbara Wilson, and Dr. Charles Menzies talking about the deep involvement of Indigenous peoples in managing their lands and waters. They focus on the return of sea otters and how this celebrated species recovery was enacted under a framework of settler colonialism. They speak in detail about northern abalone in the context of traditional and contemporary fisheries, and their interaction with sea otters. (Listen to podcast here). Listen to Part One of this series: Trophic Cascadia.

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Enabling Coexistence: Indigenous voices reveal key strategies for navigating sea otter recovery

[Burt et al. 2020] This paper compiles and synthesizes knowledge from Indigenous leaders and knowledge holders from Alaska to British Columbia through workshop focus groups and community surveys. It reveals a suite of strategies for improving coastal Indigenous people’s ability to adapt to the social, ecological, and cultural changes that are triggered by the recovery of sea otters. The findings illuminate four key strategies are perceived as critical to facilitate the coexistence of people and sea otters. (Read the illustrated summary) (Read the paper)

Can social justice & ecosystem-based management be reconciled to address sea otter recovery?

[Pinkerton et al. 2019] This paper explores how ecosystem-based management for sea otters might be advanced if Indigenous communities were viewed as components of ecosystems having rights to a sustainable future. It describes sea otter management prior to European contact and also a current co-managed system proposed by the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations. (Read the full text paper here)

Indigenous resource governance & stewardship help build resilient coastal fisheries

[Lee et al. 2019] This paper does a policy analysis of northern abalone stewardship, comparing traditional Indigenous and modern fisheries governance and management. The analysis reveals that traditional First Nations management principles for abalone are aligned with “resilience principles” whereas contemporary decision-making and management policies did not. The study suggests that Indigenous resource stewardship practices could be broadly applied to foster more resilient coastal fisheries today. (Read the full text paper here)

Sunflower sea stars play a critical role in kelp forest resilience

[Burt et al. 2018] Sunflower stars enhance the resilience of kelp forests by eating small and medium sea urchins left uneaten by sea otters. When sunflower star populations collapsed due to an outbreak of Wasting Disease, there was a 30% decline in the density of kelp forests on the central coast of BC. (Read the public summary here) (Read full text paper here)

Multiple knowledge systems reveal changes in abalone abundance over time

[Lee et al. 2018] This study combined First Nations traditional knowledge, ecological surveys, archeology data, historical records and fisheries landings to assess how abalone populations have changed over time. This data reveals dramatic declines in abalone between 1940 and 2010, but suggests current abalone populations are more abundant that in the 1800s, calling their endangered status into question. (Read the full text paper here)

Sea otters & abalone: Can our coasts sustain both?

[Lee et al. 2018] While abalone numbers can be reduced by up to 16x with the recovery of sea otters, more of them tend to hide and exist at deeper depths, in part because of the expansion of kelp forests.

Global kelp forest change over the past half-century

[Krumhansl et al. 2016] In a worldwide analysis, we found that kelp in 38 % of regions showed declines, 27 % of regions had increases, and 35 % did not net change. In contrast to the dominant effect of global drivers affecting coral reefs and eelgrass, kelp forests appear to be more influenced by local stressors. This highlights the resilience of kelp forests and the opportunity for managing them on a local scale. (Read the full text paper here)

Post-harvest recovery of kelp in changing climate

[Krumhansl et al. 2017] Small-scale harvest of the highly productive giant kelp, Macrocystis, has minimal effects on kelp biomass and recovery, and abundances of reef associated fish, yet sites with warmer seawater temperatures recover slower after being harvested. These results facilitate our ability to navigate the trade-offs between conservation, food security and poverty alleviation within the context of climate change. (Read the full text paper here)

Sea otters are size-selective urchin predators, which in turn affects kelp forests

[Stevenson et al. 2016] Size-selective predation by sea otters affects sea urchin size structure which then influences urchin per capita grazing rates. Smaller urchins each less kelp, which reduces their overall impact on standing densities of kelp. (Read the full text paper here)

Ancient clam gardens - Part of traditional management portfolios that foster resilience

[Jackley et al. 2016] Evidence form BC’s central coast shows clam gardens are just one innovation embedded within a broad portfolio of traditional Indigenous management and stewardship practices that likely conferred resilience to coupled human-ocean systems in deep time. (Read the full text paper here)

Ancient clam gardens increase shellfish production

[Groesbeck et al. 2014] Ancient clam gardens - intertidal rock-walled terraces constructed by humans during the late Holocene on the Northwest Coast of North America - can double clam production relative to unmodified clam beaches. (Read the full text paper here)

Sea urchin overgrazing drives kelp forest regime shifts globally

[Ling et al. 2015] Switches between kelp forests and barren reefs are a classic example of a regime shift. This global analysis shows that tipping points between these two states can differ by an order of magnitude in urchin biomass (ie. kelp forest collapse is much easier than kelp forest recovery). This is a management concern as recovery of kelp beds requires reducing sea urchin grazers to levels well below the initial number that caused the system to collapse. (Read full text paper here)

Rockfish bones reveal ecosystem changes & patterns of human harvest pre-European contact

[Szpak et al. 2013] Researchers measured the carbon and nitrogen isotopes within the bones of rockfish found in late-Holocene archaeological sites on Haida Gwaii as evidence to suggest that 1) rockfish in different habitats had different isotopic signatures, 2) Haida targeted rockfish from mostly nearshore waters, and 3) local kelp sources likely declined following the extirpation of sea otters during the maritime fur trade. (Read full text paper here).

Serial depletion of marine invertebrates leads to the decline of an important grazer

[Salomon et al. 2007] By weaving together ecological evidence, archeological data, and traditional knowledge we learn what is driving declines of a culturally-important intertidal chiton in Alaska. We show that 1) spatial concentration in harvest effort through time, 2) increased harvest efficiency, 3) recovery of sea otters, and 4) serial depletion of alternative shellfish prey, all led to intensified predation on chitons by humans and sea otters, and thus localized decline. (Read full text paper here)